Lili Tolnay, a recent graduate from the Graphic Design Department of the Media and Design Institute at the Eszterházy Károly University in Eger, Hungary, absolutely adores mythology and folklore and believes it to be especially important when learning about the culture of another nation. “I’m the oldest daughter of a five-children household so growing up I have often found myself in the role of the storyteller to entertain my younger siblings. And I think the love of telling stories has stuck with me ever since”, Tolnay writes.

Tolnay’s final thesis work at University was a children’s book that she wrote and illustrated herself. The book is an attempt to revive Hungarian mythology. “Folklore is a part of our past, so it’s important for us to preserve it as much as we can. Beliefs and traditions that don’t reach the next generation can easily become extinct.”

Have you ever heard of the Markoláb? What about the Mókár? Have you ever knit a scarf for a Csuma so that it wouldn’t spit into your morning tea? Have a nasty little Fene bit your ankle? No? Maybe you just weren’t been paying enough attention.

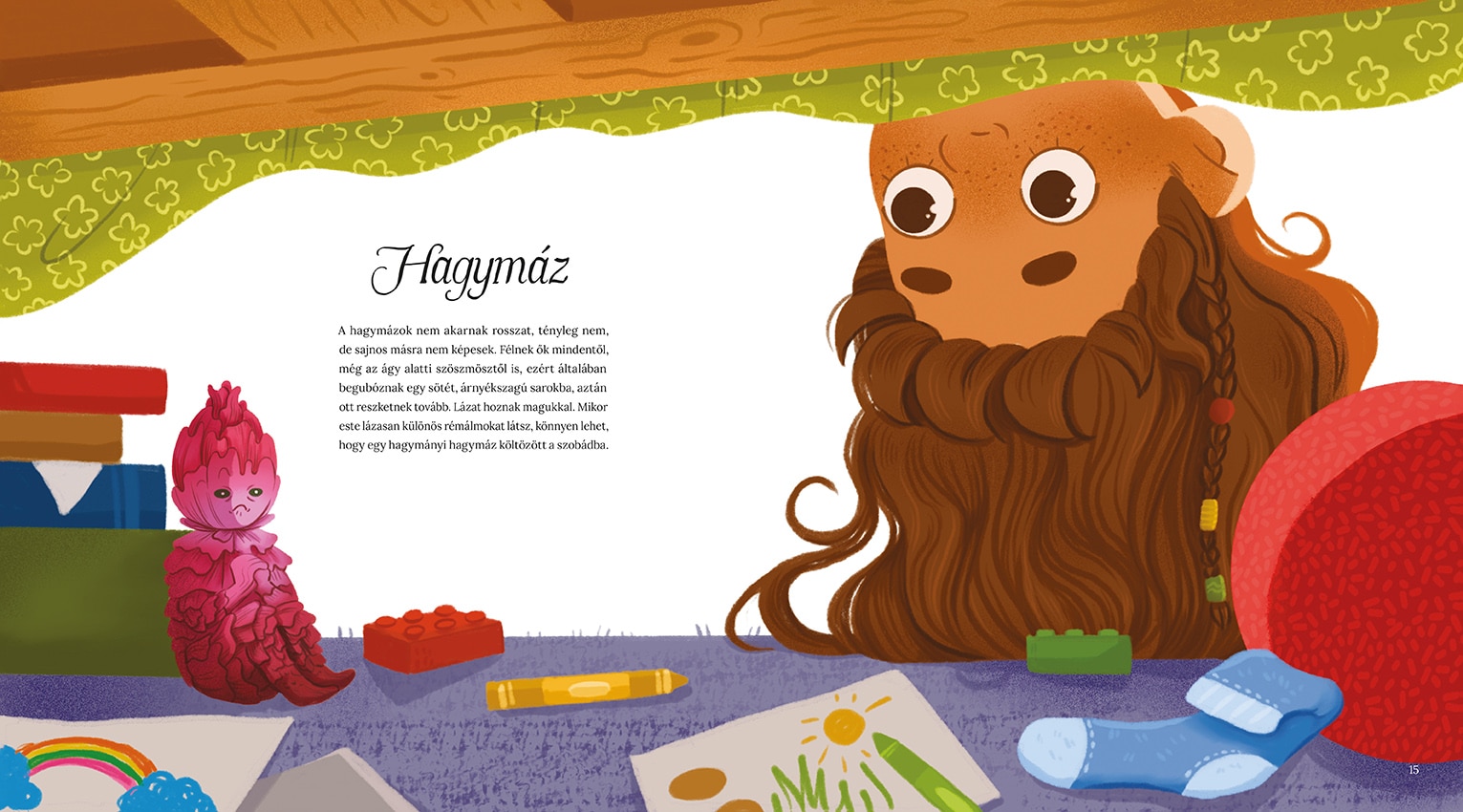

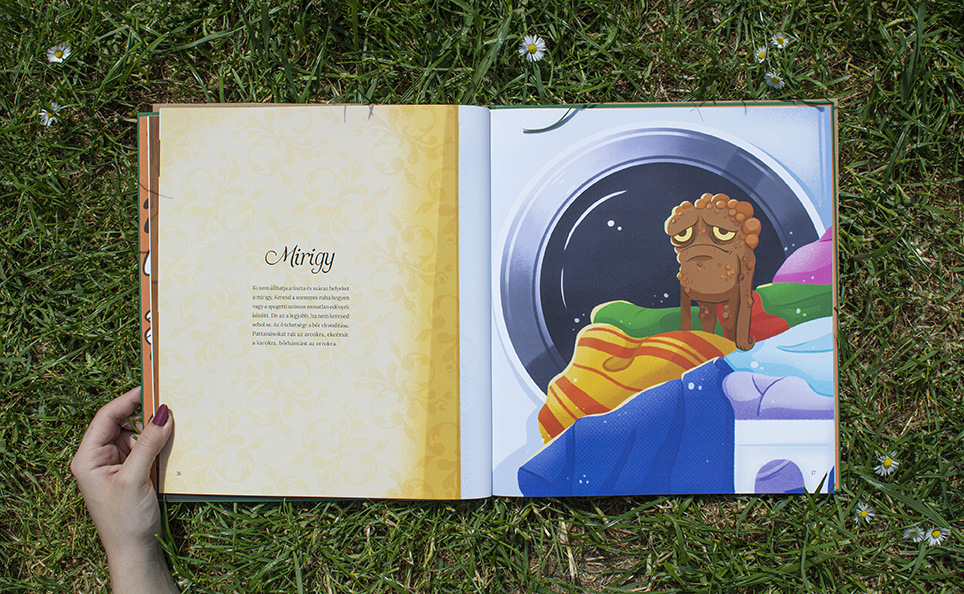

In this book, you can meet some forgotten creatures of Hungarian mythology. If you’re curious about what kind of being the Hagymáz is, or how to shake off an annoying Mitmit, then come and learn all about them! – This teaser is written on the back cover of Tolnay’s diploma project: a self-written and illustrated children’s book for elementary school-aged kids, which is a modern take on Hungarian folk religion. The book’s title Nevenincs Történet translates to A Tale with No Name.

“My aim was to take the academic texts I found during my research on the topic and attempt to make them more contemporary and kid-friendly. In my opinion, children are surprisingly receptive to various mythologies, whether they’re stories, deities, or creatures from Greek, Roman, Norse, Celtic, or any other remaining cultural traditions. We learn about them in school. But we don’t know much about Hungarian mythology so I started wondering why that is. Why do I, as a born Hungarian, know more about Greek mythology than Hungarian?”

Having studied the topic and read numerous books on the theme, an idea as to why the Hungarian education system doesn’t pay much attention to its own mythology started to become more clear to Tolnay. “I think Hungarian folklore cannot be reconstructed in the same way as, for example, Greek mythology, as there aren’t as many concrete records left as in other cultures. Not much data about our ancient myths survived most probably because of the sudden appearance of Christianity in the old, very much pagan Hungary and the new religion’s forceful spread, which demolished anything non-Christian.”

And as the church was the main carrier of literacy, the mythological beings Hungary had prior to Christianity turned into concepts that belonged outside of the religious system, and became superstitions. And while the faith placed in them became punishable, certain creatures, magical elements, and their roles merged with the new saints that came with Christianity. However, most of the Hungarian folk creatures lost their functions; their roles were taken over by the belief in one God and the fear of the devil. But the power of word of mouth managed to help keep fragments of these beliefs and stories alive through centuries. The stories, with their creatures and gods, have turned into numerous story versions – still being told today.

“With my book, my goal is to use these academic books about our mythology as a foundation, patch up the gaps, and create a version that is whole. This is my version, which of course, to some extent, is fictional. So the game of „word of mouth” continues with me.”

No detailed descriptions exist of the appearance of any of the mythological creatures, beyond the simple ‘chicken-like,’ ‘dwarf-like,’ or ‘resembling a black dog.’ Thus, Tolnay had to use her imagination. In cases where there was no descriptive material of a character’s appearance, she tried to logically contemplate how one or another creature might look. “For example, fene is the disease demon of open wounds, and there is the well-known hungarian saying ‘May the fene eat it’ so I imagined this creature as nothing but a huge mouth filled with sharp teeth, standing on four tiny legs.”

Hungarian people explain a lot of things by imagining particular creatures. The perfect example might be the sickness demon responsible for spreading various diseases. Íz is the demon of dental diseases. They are big fans of tooth decay, gum inflammation, and tartar. Almost like a Hungarian version of the Tooth Fairy, but instead of trying to steal your tooth from under your pillow, it goes straight for your mouth. Csuma is a creature that causes epidemics. Don’t leave uncovered food or drinks out at night because if a Csuma passes by it will definitely spit on them, and anyone who consumes that food or drink the next day will immediately fall ill. However, if we make a piece of clothing for the Csuma (such as a scarf, shirt, pants, etc.) and they like it, then it will just grab it and leave you alone.

The actual book, filled with colorful illustrations, is quite large with dimensions of 27 x 30 cm. The size made it difficult for Tolnay to find a printing house that would be able to produce a single copy for her. ” I was very adamant about maintaining this size to preserve the children’s book nature of my publication and in the end, I managed to find a printer in Hungary who were able to help me.” Mónika Rudic acted as Tolnay’s consultant for the project. You can see more of the recent graduates’ work on Instagram.

Images © Lily Tolnay